Become a Cybersecurity Supercommunicator

- Federico Maggi

- Communication , Security

- January 24, 2026

Table of Contents

This is the second post in a series on how to design, debug, reverse engineer, and deliver talks that land with impact in the high-stakes world of cybersecurity.

Recap. In the previous post, I explored why technical excellence alone isn’t enough—and why the gap between credibility and impact can cost your research/findings/demo its rightful influence. I busted common myths (“the data speaks for itself”), introduced the time multiplication of effective talks, and landed on a counterintuitive starting point.

😱 Start from the last slide!

Now it’s time to see these principles in action.

In this post, I’ll dissect a conference speech frame by frame, mapping its hook, setup, deep dive, and payoff—so you can steal the techniques that make audiences lean in.

I’m releasing the slides (with speaker notes) that I used—together with Pamela O’Shea—to deliver an interactive presentation for the Black Hat Community Conversations, at Black Hat Europe 2025.

The presentation is “recursive,” because (1) it guides the audience on how to design, craft, deliver an effective presentation, and (2) it shows the “behind the scenes” on how that very presentation was designed and created.

The slides themselves combine “the making” and “the result” in one deliverable. Hope you’ll find them useful, and I’m very happy to hear from you!

Fight the Craving for Templates

Unfortunately, you’ll have to bear with me because, ahem,…I haven’t prepared any slides, so I’m going make them along the way.

That was my opening (which I had memorized: more about “why” later). I wanted to capture the audience. By all means, think about your opening very carefully, because that’s your precious 30 seconds where the audience decides whether to continue listen or just doom scroll, open laptops, etc.

Anyway, now that I write this post, I recall of a business meeting that I attended where the supposed speaker introduced himself in this exact way, saying that he had prepared no slides but reassured us that he was going to “talk through the points”. If well prepared and properly rehearsed, slide-free presentations can be very powerful and engaging. In that case, the speaker didn’t prepare at all and the speech was a total disaster.

Let’s start from the template, like we all do.

I continued. And showed this slide:

Some members of the audience looked confused, but was still looking at me and I systematically made eye contact with as many folks as I could. After all, they had entered the room with the idea of learning how to make presentations. Seeing a slide template somehow made sense, but I could perceive some mild disappointment.

Tip

Never start from the template. Templates are a distraction. They feel reassuring: “oh, I already have something to start from”. They help us cope with the fear of “I don’t know where to start from”. They trick us into thinking that designing the story is an afterthought: “someone had templated it for us, so I just need to fill in the blanks with some of my content”. No!

Note on Templates

Some degree of cosmetic templating is acceptable, and sometimes mandatory in some venues (e.g., board meetings, highly polished conferences). But don’t let the structure of the template dominate your story-lining or, worse, the aesthetic of the template guide your choices.

Avoid the Temptation of Starting from the Slides

Anyway, I continued by showing the following slide. Very “peculiar” font choice and size, almost impossible to read.

With an exaggerated monotonical/boring tone, I said:

Hi everyone, thanks for coming to my talk, I’m very honored to be here […]"

My co-speaker, Pamela, who was playing the role of the speaker coach, interrupted me:

Wait, I think the font size is a bit too small, maybe the audience can’t see?

More and more confused people. I went on, and changed slide, showing the same text, just bigger.

The choice of font face was now a clear disaster.

Better now, I think everyone can read, right?

And started reciting again, using the same monotonical voice. 🥱

At this point the prank was clear but the coach played along, remarking that the choice of the font (a questionable MS Comics Sans) was somehow…unusual. This triggered some giggling. However, if your story demands to create the style of MS Comics Sans, why not?

So I showed a slide with a neutral sans-serif font face, more appropriate for a technical, no-frills presentation.

How many times you found yourself just fiddling with the slides, feeling you were making progress, while you were just changing fonts, aesthetic, decide where to put what, etc.? I pushed this a bit to the extreme, because I wanted to show the absurdity of this behavior, which I found myself falling into a few times.

Tip

Close MS PowerPoint/Google Slides/Apple Keynote and forget about the slides a this point! You’re not ready!

Most of what happens when preparing a presentation lives in the speaker notes and outside the slide deck. Learn to master the speaker notes, it’s your space! They support formatting, emojis, you can put keywords, etc.

Filler Words are Just Mechanisms to Cope with Stage Fright

The speaker coach played along and told me the font face was now better, but reminded me that “wall of text” slides aren’t a good idea (more about this later).

More importantly, the coach reminded me that:

maybe, the audience wasn’t really interested in hearing how humbled/honored/excited/etc I was in that very moment.

How many times have we heard a speech starting exactly like this?

You don’t need to thank the audience and remind them how such honor is to be there: if you’ll do a good job, the honor will come from the compliments after the talk and the audience will thank you, not the other way around.

Is it an honor to be there? Of course it is! You must feel extremely honored and excited, but acknowledging that explicitly doesn’t make you look more honored or humble. The audience will not excuse you if you’re honored, jet-lagged, tired, etc. Your delivery will speak for you. You can communicate humbleness through the way you speak.

But why do we do this? I did it many times myself!

Two reasons. One is irrational, one is technical.

- We may be scared as hell (and that’s OK!). The main reason why we come up with this “filler intro” is because we spontaneously cope with stage anxiety and we try to find “rescue” in other humans, by establishing some sort of connection that gives us the illusion of feeling immediately better.

- We didn’t prepare anything better. The second reason is that we forget to prepare a strong opening. If we have a strong opening in mind, we go with that immediately and don’t need to come up with something, risking that our emotions take control.

Tip

Prepare a strong opening—and memorize it if you need and you’ll feel more confident when walking on stage. You won’t feel the need to “come up with something” to break the silence.

Intros are Ego Boosters

I’ve seen way too many presentations starting with:

first, let me talk a bit about myself.

And then, the obligatory “whoami/About Me” slide follows, with a wall of accomplishments, fancy titles, etc.

Most of the audience don’t care: they’re here for your content. Most likely, they already know who you are. They may be coming to your talk because they know you. If not, they might have read your bio on the conference’s website.

Also, chances are that you have been introduced a few minutes before. This is the worst case, but I’ve seen it multiple times! Why repeating? If you really, really want to give your credentials, job title, name(s), etc., do it later. After a strong opening.

I may sound brutal, but we as speakers need to shift our mindset away from us.

Tip

You’re on stage to provide a service to the audience, not to directly talk about you or your company or your work as in “I did this”: these values are implicit and should come across through your content, but never explicitly.

You are there to serve your content in the best possible way. Your content will tell who you are, how much technical depth you can reach, how many vulnerabilities you can find in just one research (the one you’re presenting), to which companies/technologies you’ve been exposed (because you show examples), etc. It’s much more powerful to convey your credentials through your content, rather than reading a boring laundry list up front.

Tip

Forget your ego.

Your focus should be: what did you learn in your journey that led you to this talk and what do you want the audience to remember of your journey? Stories are more memorable than facts, and emotions make them stick better.

If you really want to tell something about yourself, you can strategically sprinkle this information throughout the story, but do not start your speech with “a little bit about yourself.” It’s just boring for the audience.

Don’t Let the “Agenda” Spoil your Story

OK so, no filler phrases, no intro. Let’s show the agenda, right? Nope! And again, countless presentations start with an agenda.

Think of a book that you’ve recently read and that you literally devoured. One of those stories that immediately hook you from page one through the end. Have you read the table of content? Did it even have a table of content?

Likely not.

Because great stories don’t need a table of content, an agenda. Would you go to watch a movie that spoils the entire plot in the first scene? What a waste of time and money!

But Why?

The reason why we tend to add a table of content is because we confuse the content design with the content presentation. You’re here to design a great story, which certainly needs an outline and careful planning, but…that’s a secret! Do you really want to spoil your great story with an agenda?

Another reason why we put the agenda is because we want to remind ourselves what we’re going to talk about, in which order, sort of a mental recap. Maybe our story is complex, so we feel that if we “prime” the audience with the outline, they’ll follow us better. But, if we think that way, we’ve already failed: If we think our story needs guidance, then maybe our story is too complex, or not well designed, or maybe not entertaining enough. I’m saying “we” and not “you” because I’ve made the same mistake multiple times.

Tip

Moral of the story is that you don’t need go guide the audience through the experience that you’ve prepared them for: your goal is to design and deliver a presentation that is so well done, that the audience will remain hooked all the time and they will remember what you transfer to them.

Give some “Behind the Scenes” Instead of the Agenda

The backstory of this talk, I told the audience, started a few months back, when my friend Lidia (who runs the Black Hat Speaker Coaching Program) and Jess (who run the Community Conversations track), asked if I wanted to run a session about “storytelling for hackers.”

I showed the original email screenshot in the slide.

Why did I show that slide? Because it made the moment real, relatable, personal. I showed my reply, where I was asking Lidia:

- what was the goal of the session,

- what audience they were expecting to target.

This may be the time when you (speaker of conference XYZ) receive the acceptance notification. That’s when you want to start planning and know what your audience is going to be.

Lidia and Jess replied saying that:

- the goal was: “Transform technical presentations from good to unforgettable, and elevate presentation skills,”

- the audience was: “Black Hat speakers and attendees.”

Map your Target Audience (in the room and beyond)

Who will you be speaking to? The target audience is not necessarily all the audience sitting in the room; it’s the subset of audience YOU want to target. You can’t reach everyone in the room. You’ll lose some folks, and that’s OK. It’s up to YOU, when you design the talk, to decide which audience you want to target.

Be realistic about who you can find in the room, though. Don’t expect to find corporate customers at DEF CON. Don’t expect many hackers at a marketing venue.

Recorded talk? This makes it trickier, because it extends the span of your audience. Maybe the recording will circulate among specific circles, or hosted in a YouTube channel followed by folks you want to target. You can speak to them, but be explicit, or your room will be confused: ≪By the way, if you’re watching this one recorded…≫

So, who are you targeting?

Audience: Prospect Customers

Prospect customers will measure your trustworthiness. ≪Can we trust this speaker (as a proxy of the organization they represent)?≫ For example, if you found vulnerabilities and your speech is about the findings, and your company sells EDRs, focus on impact and mitigation, clearly explain your findings, and avoid FUD. Skip the “how I found this” part. On the opposite side, if you or your company are selling vulnerability scanners, explaning how you turned your finding into a code-scanning rule is what they want to hear.

Audience: Press

Press is going to look at the “so-what?” of your work. They’re interested in understand what’s the impact to the broader public and they need relatable examples (or they will make up some). Be clear and frank about what you did (and didn’t find). Avoid speculation and give them some concrete examples, so that they will not have to take shortcuts and potentially bend some facts.

Audience: Peers

Your peers are the most challenging audience. Peers are going to think: “Mh, can I replicate this work?” Peers are there to learn from you, but they’re also expert in your specific field. Although this usually doesn’t happen in public, your peers are the ones asking the toughest questions: so you want to think about the weakest spots of your work and anticipate or expect questions in those gaps.

The Last Slide: Your Core Message (in 280 chars!)

Messaging is the second most important part after the audience. What message do you want to leave behind with your speech?

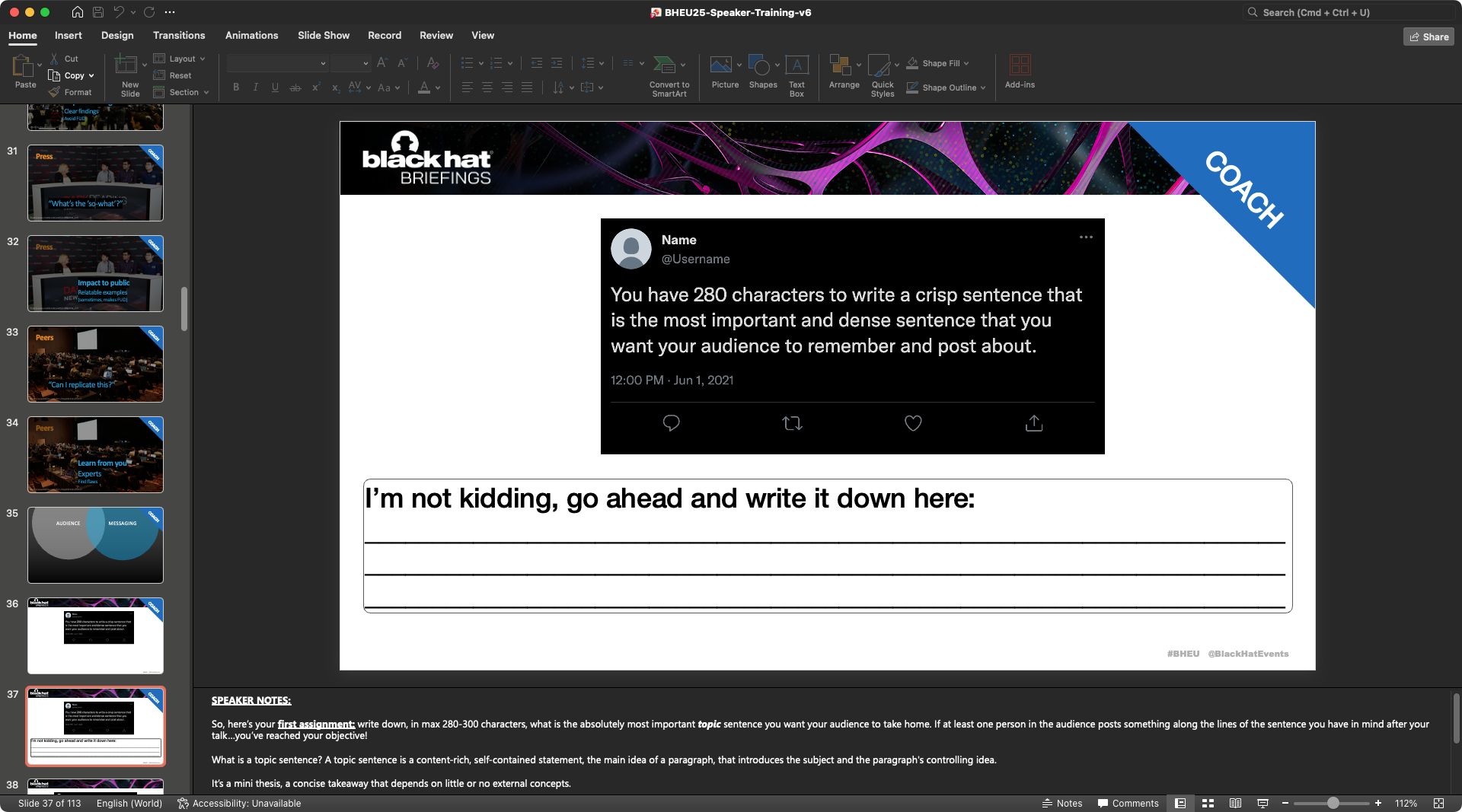

Challenge

You have 280 characters to write a crisp sentence, that is the most important and dense sentence that you want your audience to remember and post about.

When I coach speakers, this is the first assignment I give them. Write down, in max 280-300 characters, what is the absolutely most important topic sentence that you want your audience to take home. Imagine that someone in the audience leaves the room after your presentation and posts something quick about your talk. What would you want that to be?

What is a topic sentence, by the way? A topic sentence is a content-rich, self-contained statement, the main idea of a paragraph, that introduces the subject and the paragraph’s controlling idea.

It’s a mini thesis, a concise takeaway that depends on little or no external concepts.

The key takeaway stands on its own.

In a world overloaded with information, coming up with good takeaways is fundamental. Think about great talks that were tweeted about a few moments after. Writing the takeaway sentence is something that you should take very seriously, because the rest of the presentation will blossom out of it. Write it down, revise it. The takeaway should be finalized no later than 4 weeks before the talk day.

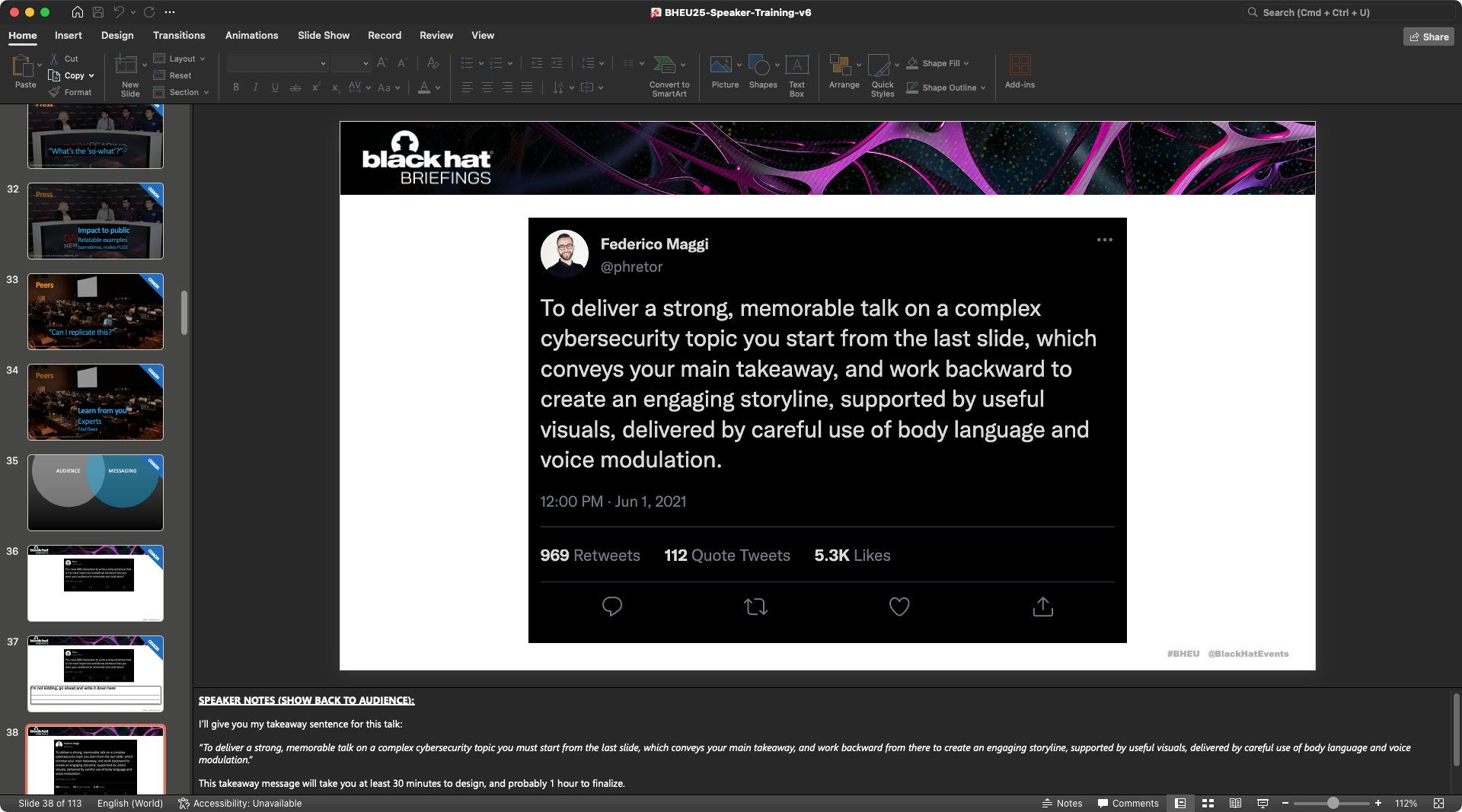

To pull the curtain, I gave the audience the takeaway sentence that I had written for the talk I was delivering:

Now I may know what you’re thinking…that I’m taking an easy win here, because the content I was delivering wasn’t very technical (as in “computer hacking”), and so it’s easy to craft a good takeaway message.

(pause)

I disagree.

Every content can be “technical,” in the sense that you can make it complex enough to require infinite time to be delivered—and a long/complex takeaway that nobody will ever remember.

It is difficult to pick and decide what to ignore. It’s very tempting to go through everything. But you don’t have time: so, you need to choose, you need to decide, up front, what you want people to remember.

Assuming you’re preparing for a conference to which you submitted a proposal, you’ve already made a choice. When you prepared your abstract, outline, etc., you’ve selected how to “sell it” to the review board in the best possible way. Of course your content has to be strong, but you carefully choose what to highlight so that the strength of your work is not diluted.

Now that you’re preparing your presentation, you just have to do the same. You’ll have to leave something out, reframe something else. You select what you want the audience to remember.

Breakdown the Core Message into 3+ Sub-messages

Now that you have your takeaway message polished, what should you do?

You need roughly 3 topic sentences (again!) that support your main takeaway sentence. Those must be designed in the same way you designed the main takeaway sentence.

Here’s the second assignment I give to the speakers I coach: break down your takeaway topic sentence into 3. You should be able to identify 3 elements that are worth digging into. If you can’t, then maybe your takeaway topic sentence isn’t good enough and you need to iterate and rethink it. For each element, write a crisp, supporting sentence.

I told the audience that, while designing the talk they were attending, I had identified 4 parts:

- Sub-message 1: “start from the last slide.” Design your takeaway message at the intersection between your research and the audience to maximize resonance of your presentation. (That’s what I had just finished presenting.)

- Sub-message 2: “work backward to create a story.” Create a storyline based on the 3+ messages that support your takeaway. (That’s what I was doing right in that moment: I love recursion!)

- Sub-message 3: “visuals support your narrative.” Visuals must support (not dominate) your narrative and must be designed and sequenced to explain and clarify, not overwhelm.

- Sub-message 4: speak with your body and tone. Body language is what we perceive first; tone of voice and modulation convey emotions.

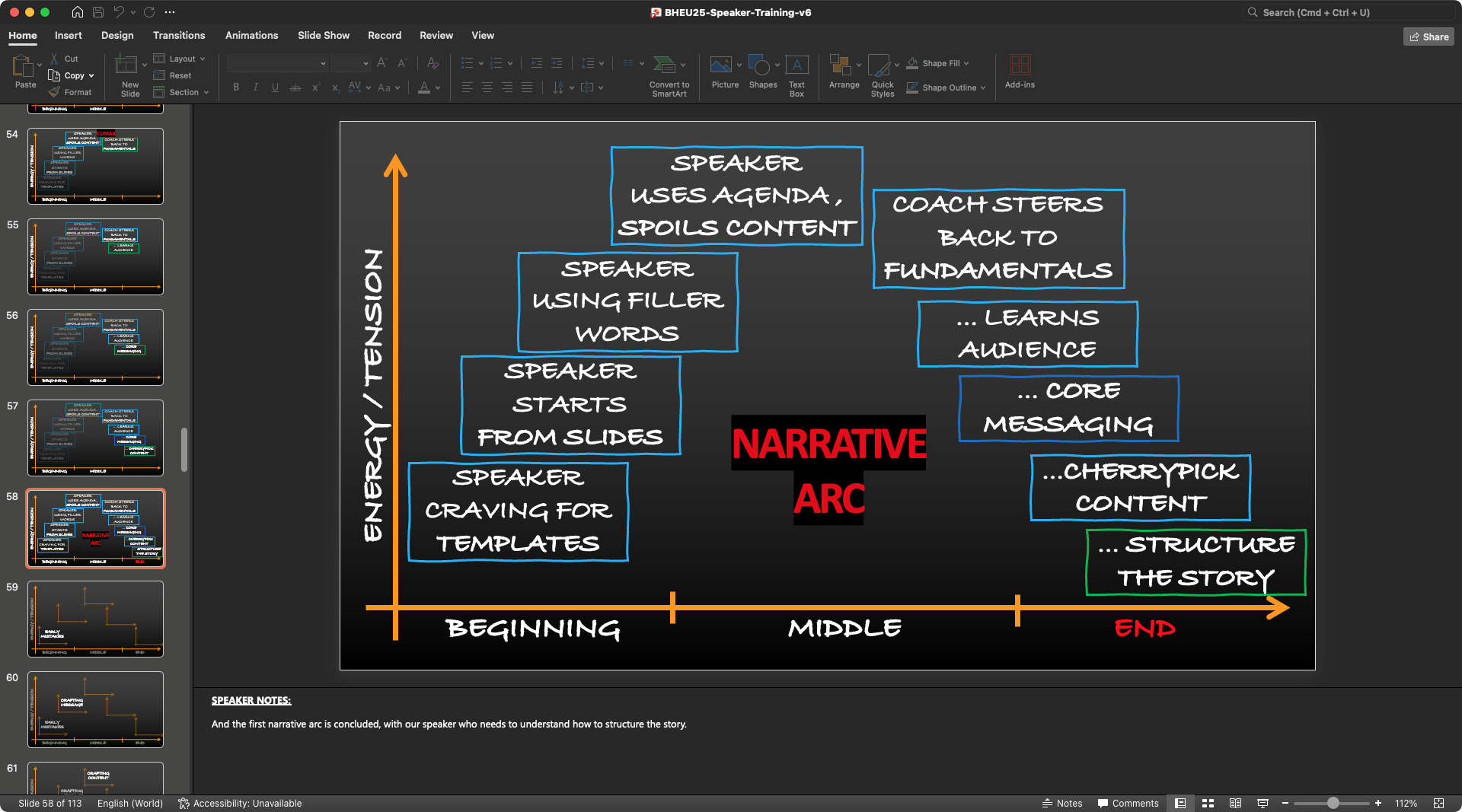

Work Backward to Create a Story: Use Narrative Arcs

When designing a story, narrative arcs work like stimuli for the audience’s brain. A “flat” linear story isn’t entertaining. A series of narrative arcs keep engagement high.

- When I created this story I had a “speaker craving for templates” in mind. That’s me, remember? In your case, it could be the beginning of the story of how you found “a vulnerability that was particularly hard to work on”.

- In my story, this speaker starts from slides, piling up multiple mistakes. The tension starts to build up. The narrative arc is in the ascending phase.

- This speaker uses the agenda to reveal the talk and spoil the story. More tension. And as we go on, the energy level, the tension grows.

- Until we reach a climax and the coach intervenes to correct the speaker, telling the speaker to go back to the fundamentals.

- Our speaker now learns about the importance of the audience.

- And the importance of crafting a core message.

- And learns to cherry pick content they want audience to remember.

- And the first narrative arc is concluded, with our speaker who needs to understand how to structure the story.

And the entire story of your speech is made by stacking many mini-arcs.

Visuals that Support Your Story (not dominate it!)

While designing the slides that I release with this post, I packed them with as many visual techniques as I could, so you can get inspiration and hopefully get more creative.

How many slides and visuals should you use? As many as your story needs. No more, no less. Your story must dominate the visuals, not the other way around. That’s why you never start from designing the slides, unless you already have a clear core message and storyline ready.

Yeah but I have code & stuff to show…

Avoid the “Wall of Code”

This is a common case in cybersecurity presentations. If your story is about how to exploit Log4j or Spectre, you may need to show some code. But you don’t have to show the whole code! You need to remove everything that is not essential. This is a very common pitfall: showing “more code” or “intimidating walls of code” is just…decoration! Does it deliver any message besides “lots of confusing code?” Be honest.

Let’s take Spectre as an example. I could have shown this code, which is already quite short.

while (1) {

// for every byte in the string

j = (j + 1) % sizeof(DATA_SECRET);

// mistrain with valid index

for (int y = 0; y < 10; y++) {

access_array(0);

}

// potential out-of-bounds access

access_array(j);

// only show inaccessible values (SECRET)

if(j >= sizeof(DATA) - 1) {

mfence(); // avoid speculation

// Recover data from covert channel

cache_decode_pretty(leaked, j);

}

}

Draw Attention Instead

Do you think that’s good enough? I think we can do better. You could focus more and only show these lines, because they take seconds to read and understand.

If you put more code at the same time, you’ll lose your audience: their brains will unavoidably start processing the code and your voice will be lost, while you want to keep attention high.

for (int y = 0; y < 10; y++) {

access_array(0);

}

Can we do better? Yes, because in this code, there are only 2 important points to support the narrative that we assume you designed.

- repeat N times

- access array

............... y < 10; .... {

access_array(0);

}

So, you could highlight those with a colored box or other visual tricks. That’s it. It’s super clear, and if the audience is interested in seeing more, they will reach out!

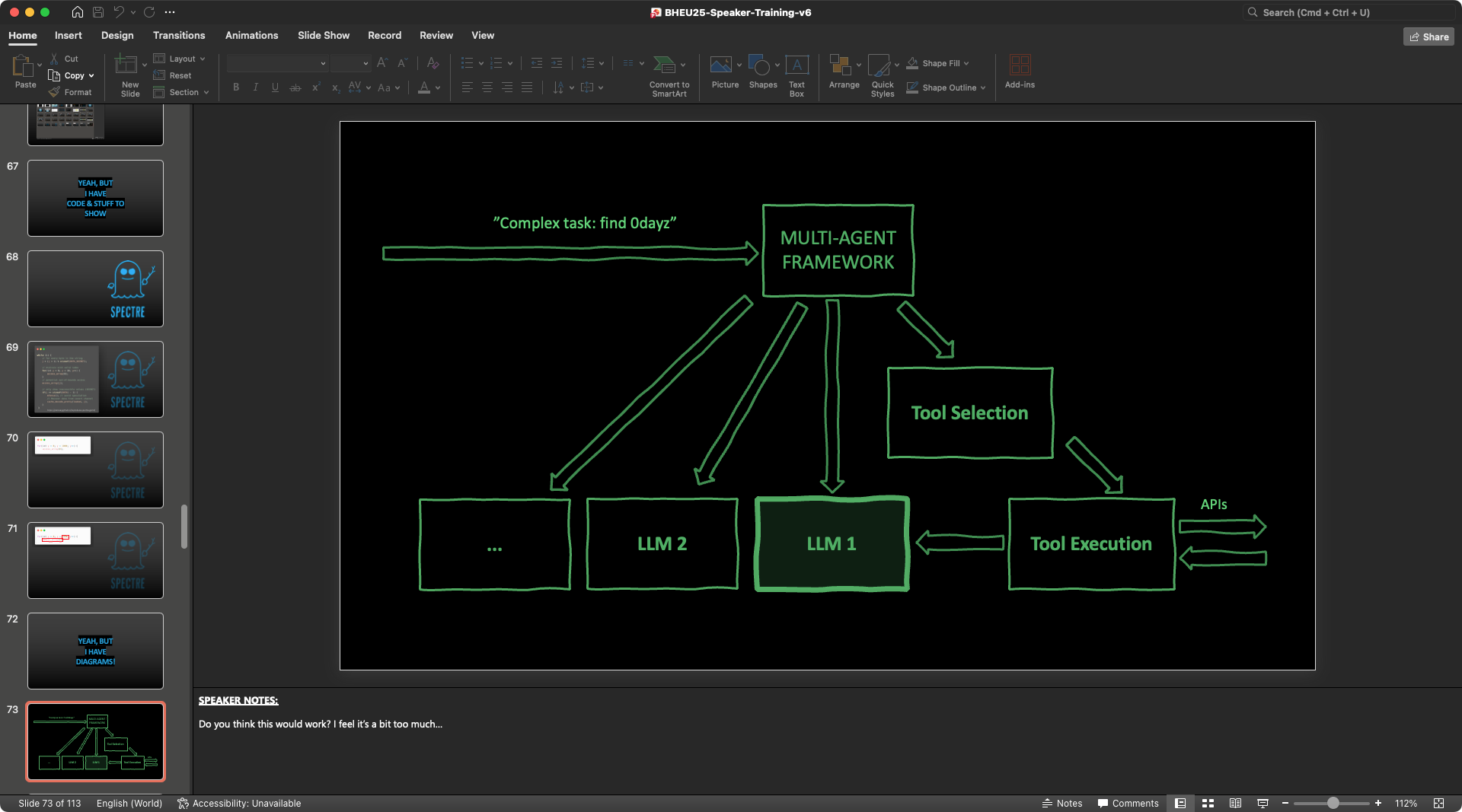

Yeah, but I have lots of diagrams to show…

How to Make Good Diagrams?

Here’s another common example where visuals could dominate and not support the story. Don’t focus your attention on making diagram look good. Focus on making them “useful for your story.”

For example, this diagram isn’t fancy at all, it’s just a few plain lines. Also, it’s pretty useless and distractive in its current form, because it overwhelms the audience: “Where do I begin? Top right, top left? What is it? I’m scared, I’ll look away.” That’s what happens inside our brain.

Show Complex Visuals Incrementally

The easiest way is to just show complex visuals incrementally. Build them “with the audience,” step by step. And no, you don’t need any animations, you just need to build the entire diagram first, and then duplicate the slide N times (N steps). Then, go to the first copy and delete everything but what you want to talk over in the first step, and so on.

Alternatively to deleting selectively, you can create rectangle shapes filled with the background color and use them to cover everything but the area around the element you want to talk over in the first step.

Should you use Animations? Or PowerPoint “feature XYZ?”

Maybe!? Only if they serve your narrative!

If you need to emphasize something, like, instructions going from the virtual CPU to the physical CPU, then yes. If the focus of your narrative is to explain that instructions aren’t executing in the virtual CPU but they’re actually running straight into the physical CPU core, then a simple animation delivers the message clearly.

What About Videos? Demos?

Again: a video, a demo, anything, is there to serve a purpose. Do you need a video or a demo AT THAT POINT IN TIME? If yes, then insert it.

About Live Demos

Do you need to make the demo live? Maybe, maybe not. You can pre-record it. There’s nothing bad about it. Is your goal to impress the audience to show them that something can be performed live? Then if that is your objective, sure, go ahead and do it live.

Like in most cases, if your goal is to demonstrate that a certain technique/tool can be made to work in a specific way, then you can just pre-record a short clip and embed it in the slides. So many things can go wrong on stage: it’s a real pity when a demo doesn’t work and it stresses you out for nothing. “Oh, I hope my demo works…it worked last night. Lol!” Why? Just…why?

Warning

Here’s another common mistake. Have one, big, demo toward the end, involving many steps. Why not splitting the demo into small bite-sized clips throughout your story? You keep attention high and re-inforce the understanding of what you’re explaining. It’s a very strong technique compared to hoping that the audience will remember everything you said 20 minutes before and follow the very same steps during the demo.

Oh, and if you embed a video, make it fullscreen on the slide. Use the entire real estate! And make it auto-play, or “play when clicked,” so you don’t need to go back to your laptop (especially if walking on stage), fiddle with it, move the cursor around to reveal the player, excuse yourself for not being able to find the button, say obvious things like “oh, let’s see if I can find the button” or “let’s see if it works.”

C’mon!

Use Body Language, Modulate Your Tone

We speak with our body, facial expressions, tone, and words of course. Theories about what prevails between body language vs. spoken language have been debunked for lack of support, but we can confidently say that consistency and combination matter. Again, there’s no right or wrong: Focus on the intent of your story.

Let’s see a couple of examples.

Never turn your back to the audience?

Why not? Why yes? If your intent is to entice the audience to read a long fragment of text you’ve intentionally put on the slide (because your story needs the audience to read), or if you’ve put a video for the audience to watch…well, it’s perfectly OK—and actually a pretty powerful move—to turn your back to the audience and “be” part of the audience for the duration of that segment.

Tip

We imitate each other, and if the leader of the conversation (speaker) does something, the audience will notice and will tend to follow. If I project a fragment of text that takes 30 seconds to read, but I stare at the audiece without reading, most audience won’t read (see about observational learning). Instead, avoid the midground: do not face the audience and use a finger or laser pointer to aim at what you want the audience to read, because this creates an inconsistency between your body language (face the audience, do not read) and your spoken language (read).

Podium vs. Stage

What if I’m on stage with my arms crossed, my feet pointing inward, my head slightly tilted down, reading on my laptop screen behind a podium? I’ll be a lateral presence of my speech, the narrator, not the main character. If that’s your intent (e.g., you’re delivering someone else’s talk, reading a poem), that’s perfectly OK to keep your status “low key.”

Tip

However, if it’s your story, your research, and you’re passionate about it, you should rather be your story, right in the middle of the stage, using your arms and full body when the story requires it. It’s much more immersive for the audience to see the speaker “living” the story rather than passively narrating it.

Be Aware of Unconscious Movements

Our brain is phenomenal at coming up with coping strategies pretty fast. If we’re nervous or anxious, we may find ourselves unconsciously tapping our fingers, clenching our hands, pacing back and forth on stage, swinging on a chair or on our left and right leg…at a very regular pace. The “regular pace” is what makes these unconscious movements soothing for our brain, it calms down the negative emotions.

But it’s terribly annoying for the audience to watch! Imagine watching a giant pendulum swinging left-right across the stage.

Developing self awareness of our movements takes time, but it’s pretty easy with some practice. Just record your rehearsal. Not only it’s a great way to rehearse and improve, you’ll become more and aware of little oddities (we all have some!), the tone of your voice, etc. Try it!

Use your Voice as your Instrument

Would you listen to a monotonic, regular, flat music for 30 minutes or so? It’s great if you want to fall asleep, but not quite entertaining nor energizing.

Like narrative arcs keep the story flowing and create dynamicity, up-down voice modulation creates and release tension, suspance, energy, joy, etc. If you convey emotions, your story will stick. I’m not saying that you should act and go beyond what’s comfortable with you and your style, but being aware that a flat tone puts people asleep should be enough to convince you to work a little bit in the opposite direction.

You want to keep your voice moving.

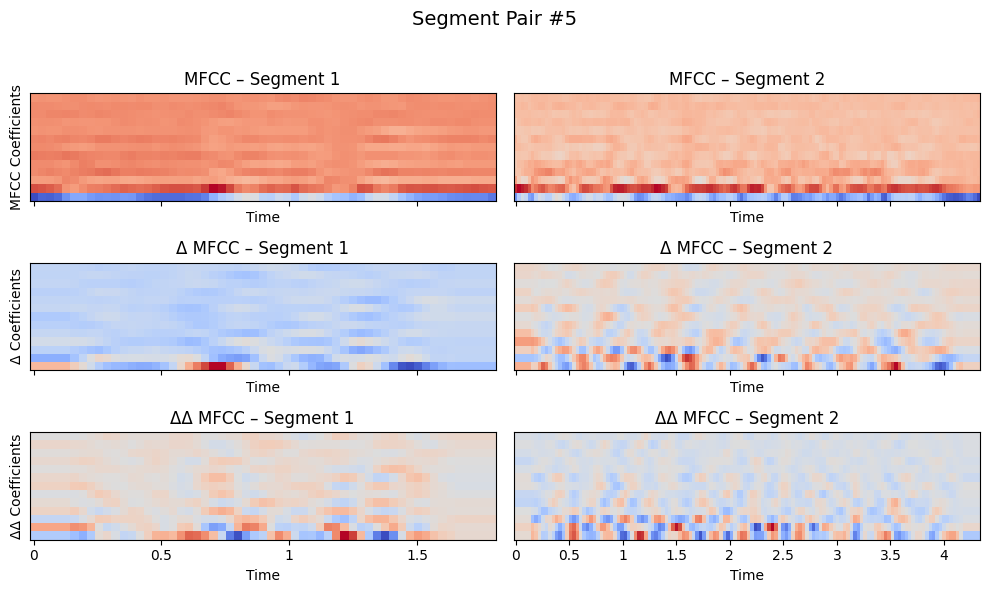

If you’re curious, you can find out how much your voice is moving by recording yourself and extracting the MFCCs (mel-frequency cepstral coefficients) features. These features summarize the shape of the short-term speech spectrum (roughly: timbre, vowel quality, resonance) every ~10–25 ms. The delta MFCCs are the time-derivatives of those coefficients, so they capture how quickly that spectral shape is changing. I’m pretty sure these are some of the features that the various “speaker coaching” apps extract to tell you how much “engaging” a speech is.

I was curious so I’ve hand-picked a few great talks and extracted their MFCC delta coefficients and trained a NN on telling speeches apart based on these features. With just about 100 samples, a tensor classifier was able to tell “engaging” vs. “boring” speeches with 98.6% accuracy, meaning that these features are pretty powerful in capturing this aspect.

On the left, you see an “entertaining” segment. On the right, you see a “flat” segment. You see the difference?

I ran the analysis on the DEF CON 32 dataset and the results motivated me to put together this blog post. I’ll release the scripts to reproduce.

Getting Ready: Beyond Content and Delivery

Let’s take a look at some practical tips to get you ready for your big day. From now on, we assume that you’re clear on the following:

Messaging (1+ months before the talk):

- target audience nailed down,

- core message written down,

- 3+ sub-messages written down,

- legal/disclosure aspects settled.

Core material & story drafted (1 month before the talk):

- core message is final and you’re convinced of it,

- supporting messages are crisp and clear in your mind,

- outline is 90% final,

- sources for illustrations are 50-70% identified,

- demos are 80% done,

- no slides are done yet.

Core material & story done (3 weeks before the talk):

- outline is 90% final,

- outline is moved to speaker notes,

- simple illustrations are drafted on paper or on slides,

- complex illustration are described with placeholder text on the slides.

Content finalized (2-3 weeks before the talk):

- slides 90% final,

- 1 recorded rehearsal every 1-2 days,

- slides and/or speaker notes improved immediately after each rehearsal.

Now, the big day is approaching. Let’s say it’s about 1-2 weeks away. What should you do?

Know Where you’ll be Speaking and Plan Around That

Learn to know and manage the stage, because you’re going to be spending a good hour on there. Talk to the organizers and ask if they can send you a layout of the room. They must have it. Ask where the podium is going to be (if you need to use it). Ask if you’re going to be miked up or you’ll have to handle a microphone.

How big is the stage? Is there a prompter? Can one be set up? And if you need a special arrangement to feel confident on stage, just ask for it! There’s nothing bad about using a prompter: if you practice well enough, you won’t need it, but for complex presentations with many transitions, it helps.

If you’ll have a prompter and want to use it, you’ll have to ensure the tech person is aware and that you’ll have the possibility to stream to two monitors (current slide on one monitor, next slide + speaker notes on another).

When planning your trip, block some time the day before to visit the room you’ll be speaking in. It never occurred to me that there wasn’t any exceptions or other issues to sort out: better do that on the day before than 10’ before the speech in panic mode.

Rehearse 3+ Times 1-2 Weeks Before the Big Day and Tweak Your Slides

Mark your calendar so that you block at least 3-5 time in the 2 weeks before your talk. Right after you rehearsed, you must ruthlessly edit your slides and speaker notes, immediately after each rehearsal. You don’t say “I’ll do it later,” because you’ll move on with your day and you’ll lose momentum. Allocate 1.5x the duration of your speech so you’ll have some time to tweak the slides.

Rehearse the Day Before the Big Day: Don’t Touch the Slides

Find a room similar to the one you’ll be speaking into and do a couple of rehearsals, especially if you have a co-speaker. This is fundamental!

The goal here is to reduce as much as possible any surprise effect, and familiarize as much as possible with the environment. Best if you could rehearse on the exact same room, so you’ll have time to do a tech check, maybe even with the technician.

Set Alarm Clocks: Get Sleep

I tend to get distracted by the many social activities around conferences and I want to enjoy them without having to worrying about time. So I set an alarm clock to remind me of when it’s time to call it a night and go to bed to get some sleep. I don’t recommend rehearsing before bedtime because that lits up your brain like crazy and you’ll just spend time touching up the slides, rehearsing one more time, and (at least for me) that’s the recipe for an interrupted, low-quality sleep.

Set an early alarm clock so you can rehearse first thing in the morning.

Rehearse the Day of the Talk, First Thing in the Morning

As soon as I wake up on the day of my talks, I get myself together quickly and rehearse. Why? Because I know that if I’ll leave it for later, I’ll walk down for breakfast, find someone and chat, enjoy the conversation, and just forget about it. I really like this social aspect of conferences, don’t get me wrong, but I find myself enjoying these moments when my mind is free from other thoughts.

So, my recommendation is just to be done with your last rehearsal before you leave your room. Of course, absolutely no adjustments to the slides are allowed! Well, if your legals call you with a last-minute update, maybe yes. 😬

The 2 Hours Leading to Your Speaking Slot

Here’s what I do in the ~2 hours before my recent speeches (the ones I felt well prepared and relaxed).

- 2 hours before: locate the room and know how to get there from “anywhere” in the conference venue. It’s very easy to get lost in large conferences, and you don’t want to be late. Check out the Las Vegas Black Hat venue you’ll quickly realize that it’s a multi-floor beast that takes you at least 20 minutes to go from room A to room B unless they’re adjacent; because even if two rooms look close to each other, they’re not; and if they are, there will be rivers of people blocking your way.

- 1 hour before: use the restroom, do a bit of stretching, including facial muscle stretching: of all muscles, speaking is putting your facial muscle at stress. Stretching before a long speech helps reducing that stiffness feeling, dry mouth, etc. If you’re curious, just search on YouTube for facial muscle stretching, like this one, or this one. I know, you’ll feel awkward and funny at first.

- 30 minutes before: if your opening is complex and you feel you need to memorize it again, I repeat it multiple times out loud.

- 10 minutes before: test the clicker, ensure it changes slides as expected, get miked up, take a sip of water (not too much!), and get some candy. Speaking is a physical and mental effort: you’re going to need sugar. And nobody wants you to faint on the stage (it happened). Also at this point, close all your apps except PowerPoint (or whatever app you’re using), and set all your devices to “do not disturb,” silence all notifications, etc.

- 5 minutes before: repeat the first sentence of your opening out loud. This is your hook. Don’t worry about the rest: It will follow naturally, because your brain will perform an “index lookup” operation based on the first words you’ll say.

- a few seconds before: you’re on stage. Do not focus on your laptop screen. Stare at the audience. Embrace the feeling. Make eye contacts with some of the people here and there (don’t fixate on one!), smile. This also prepares your eyes for the stage lights, which can be quite bright. If you’re 100% focused on your screen and think about what you have to say, and then realize that you’re talking into the lights, or that you have a thousands pairs of eyes staring at you, it’s completely human if you may feel a bit dizzy. So, the more you familiarize with the feeling, the better it gets every time.

Next up?

Have a talk in mind you want me to dissect? Send it over!

Need speaker coaching? Get in touch!

Downloads

As promised, here’s the slide deck. It’s quite heavy.

️💾 Grab the slides (224M)References

- C. Duhigg, Supercommunicators: How to Unlock the Secret Language of Connection, Large type / Large print edition. Random House Large Print, 2024. https://charlesduhigg.com/supercommunicators/

Note: Image generated by Nano Banana Pro (via Google Gemini) with this prompt: Generate an extremely photorealistic image of an enormous, beautiful, modern conference room, with futuristic colors with a slight touch of vaporwave aesthetic. Viewpoint of the speaker. The audience is cheering to the speaker. No podium, no speaker laptop, no clicker are in sight. Not all audience is cheering, but most of it is.